No matter how tightly developers are committed to their current project hosting provider (GitHub, GitLab, GNU Savannah, or whatever), new ones will come along over time. The history of web services is replete with turnover, and project hosting forges all follow the inevitable trend. But the cost of migration is formidable: It’s quite easy to setup a new project host like GitLab, but how do you move the whole structure of your team’s code, branches, comments, issues, and merge requests into their new home?

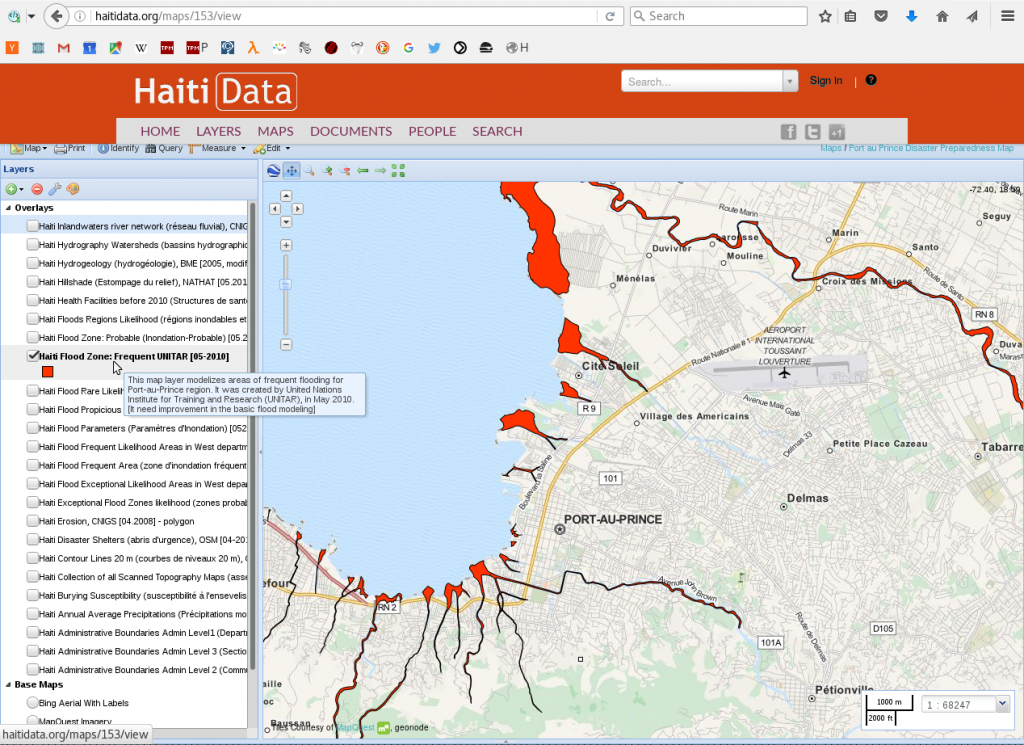

Software Heritage, a non-profit with the mission of archiving free software code, faced this daunting challenge when they decided to move from Phabricator to the more vibrant GitLab. For a while, a lot of free and open source projects had found Phabricator appealing, but the forge had been gradually declining and officially ceased development in 2021.

At OTS, we developed an open source tool and framework to support migrating to a new project hosting platform. We used it to move all of Software Heritage’s projects from Phabricator to GitLab, but the framework is robust enough to support migrations between almost any project hosts.

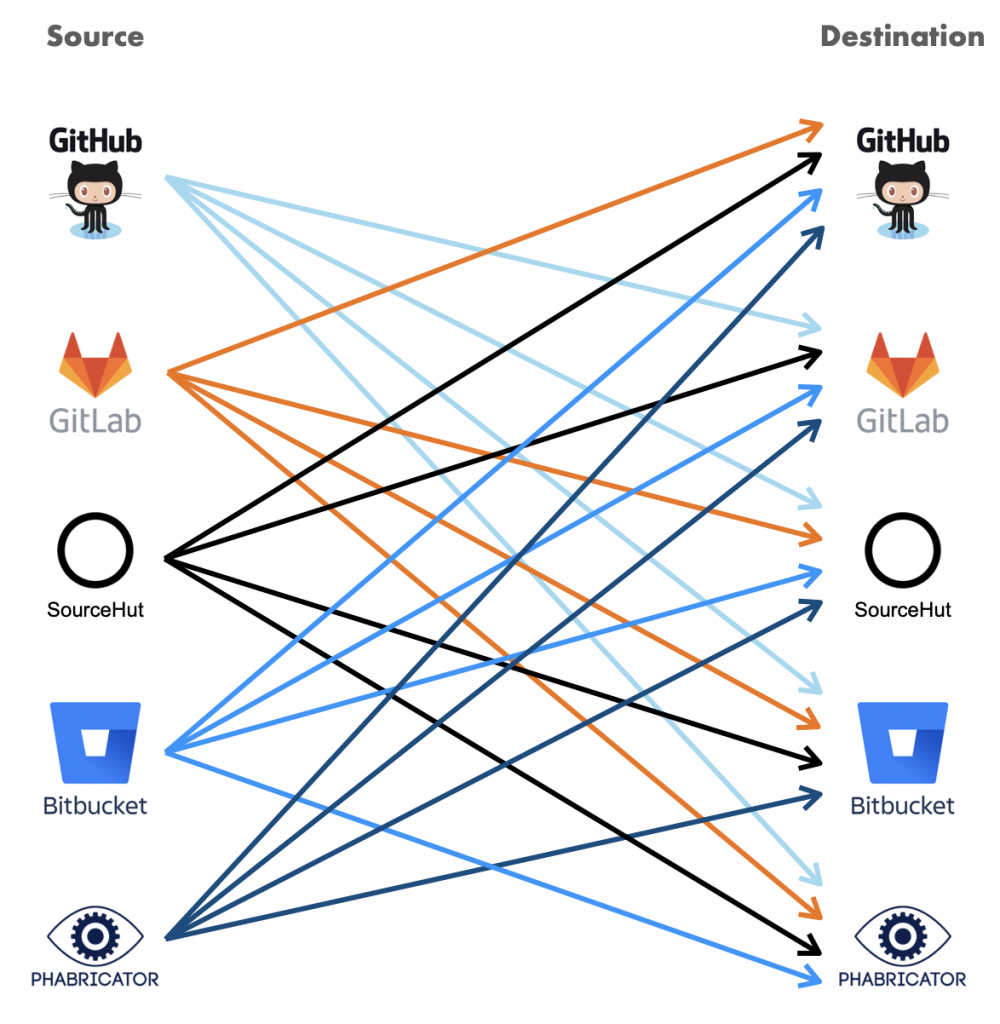

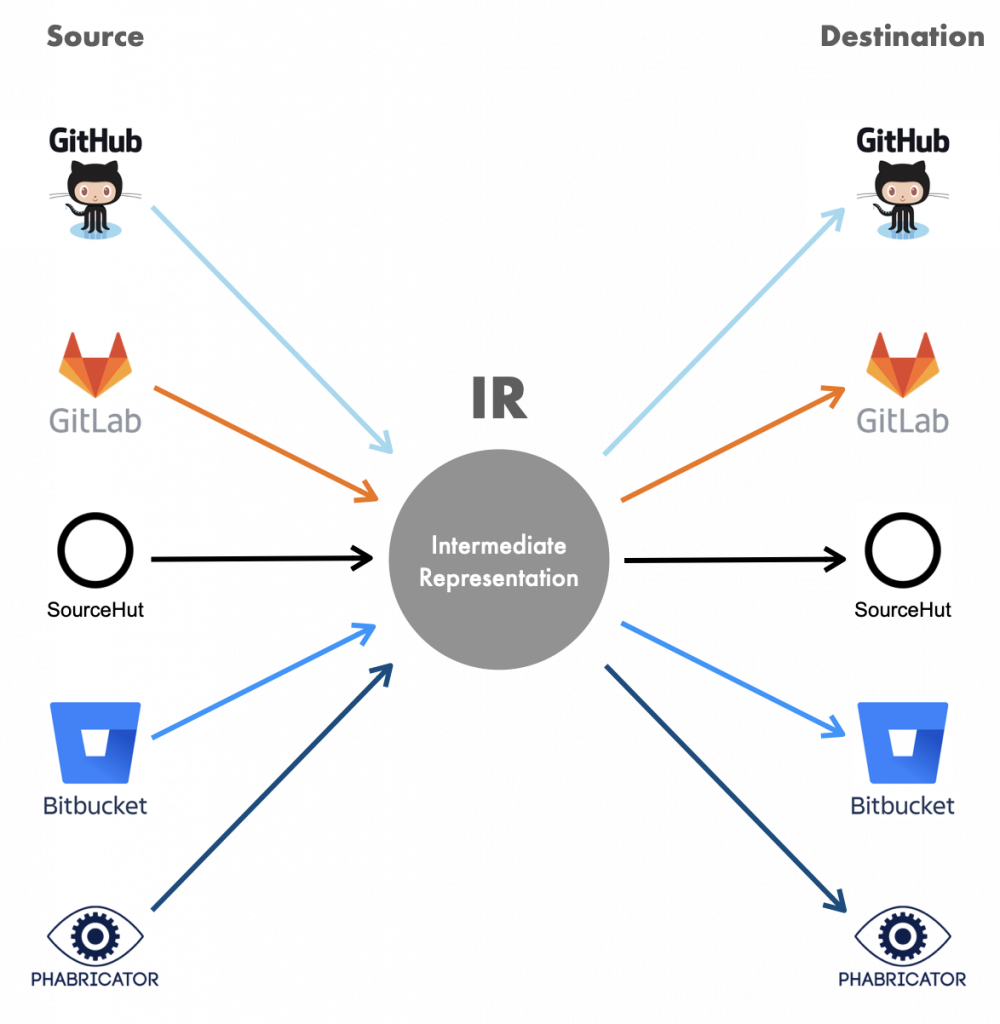

The tool is called Forgerie. Its goal is to automate the migration of projects from one hosting system to another. Forgerie is extendable to any source and destination. It translates input from a project hosting platform into a richly-featured internal format, then exports from that format to the destination platform.

This is the same method used by many tools that perform n-to-n migrations. For instance, the health care field contains many incompatible electronic record systems, so migration tools usually create an intermediate format to cut down on the number of necessary format conversions.

OTS continues to work on Forgerie as part of its offering of migration services to clients. If you would like to use Forgerie, please grab it from Forgerie’s GitLab page or contact us if you would like help with a migration.

The rest of this post offers some technical background on Forgerie. It should be of interest to anybody solving similar project hosting problems or, more generally, to anybody working on moving structured data into a new data store. Many migration projects fall into the traditional category of Extract, Transform, Load (ETL), but the richness of data stores today stretches the category into new realms.

Forgerie

The Forgerie code was initiated by OTS developer Frank Duncan and released under the GNU Affero General Public License v3.0. This post delves into the project goals along with suggestions for the future of this project. We’ll look at the difficulties posed by this major migration project and how we handled them. This story may offer lessons and tips to people dealing with all kinds of data migration.

If you have used a project hosting system, you might well be imagining the massive requirements for even such a limited project. Code in a forge exists in many branches, each created by multiple commits and enhanced by merges. Numerous issues (change requests) have been posted by different users, along with comments that refer to the issues by number. Commit messages also link and refer to the numbers of issues and branches.

The need for a general project hosting migration tool

Tools for importing projects exist for various project hosting platforms, but they are limited. GitLab does a pretty good job importing a repository from GitHub, and GitHub from GitLab, and both allow the uploading of a private repository. Later in this article we’ll examine one particular limitation of all these import tools: handling multiple contributors.

To automate the migration from Phabricator to GitLab, Software Heritage contracted with Open Tech Strategies (OTS), a free and open source software consulting firm. Preliminary research turned up a few tools claiming to perform the migration, but none of them did a complete job. And each migration tool works only with one particular forge as input and another as destination. OTS decided to design its new tool as a general converter that could be adapted to any source and target repositories.

Migration thus requires the automated tool to reproduce, on the target forge, all the projects, branches, commits, merge requests, merges issues, comments, and users recorded in the source repository. If possible, contributors should be associated with their contributions.

OTS chose to create Forgerie in Common Lisp, which seems like an odd choice in the 2020s. But Common Lisp is well-maintained and robust. Its big advantage for the Forgerie project was that Lisp makes database-to-dictionary conversions easy. Because Phabricator stores data in a relational database, database-to-dictionary conversions were the central task in automating the migration.

The Forgerie project has three subdirectories: a set of core files used by all migrations, egress files for Phabricator, and ingress files for GitLab. This design leaves room for future developers to extend the project by adding more ingress and egress options. In order to go from Phabricator to GitHub, for instance, a maintainer can reuse the existing core and Phabricator directories.

Impedance mismatches create challenges

All forges offer basic version control features, along with communication and management tools such as issues. But each forge is also unique. In this case, Duncan had to decide how best toaccommodate features that differ or are missing in the target GitLab platform.

The biggest challenge Duncan faced is that GitLab maps projects to repositories on a one-to-one basis, whereas Phabricator treats a project as a higher-order concept. A project in Phabricator can contain multiple repositories, and a repository can be part of many projects. Phabricator also supports multiple version control tools (Git, Mercurial, etc.). Making Forgerie flexible enough to smooth over these types of differences in data structure was a key goal.

The different approaches to projects introduced several complications. First, Duncan had to make sure that each message and ticket pointed to the right GitLab project.

Merge requests were the hardest elements to migrate, because in Phabricator a changeset can span multiple repositories. The requirement that Duncan had to implement was to preserve the sequence of events in the original forge strictly, so that issue 43 in the old forge remains issue 43 in the new forge. That way, any email message or comment referring to the issue still refers to the right one.

Lots of details had to be tidied up. For instance, Phabricator has its own markup language to add rich text to comments and issues. This language had to be converted to Markdown to store the comments in GitLab.

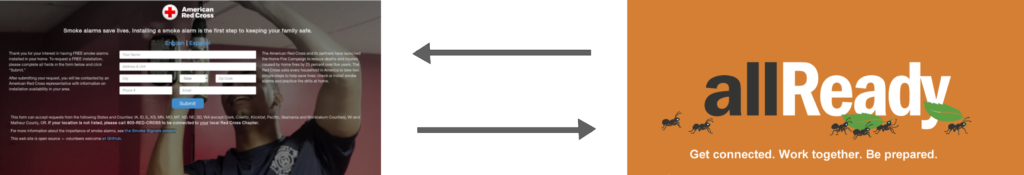

The question of multiple contributors

When there are many people to credit for their contributions, the import tool has a tough nut to crack. Awarding credit properly is crucial because many contributors rest their reputations on the record provided by their contributions. Statistics about the number of commits they made, the “stars” they got, etc. undergird their strategies for employment and promotions. Losing that information would also hurt the project by making it hard to trace changes back to the responsible person.

On the other hand, security concerns preclude allowing someone to import material and attribute it to somebody else.

GitLab solves this problem if the input repository is set up right: The person doing the import needs master or admin access and has to map contributors from the input repository to the destination respository. If access rights don’t allow the import to add material to a contributor’s repository, GitLab’s import can accurately attribute issues to the contributor, but not commits.

Forgerie goes farther in preserving the provenance of contributors: It keeps track of Phabricator users and creates a user in GitLab for each user recorded in the Phabricator repository. The Software Heritage project did not present difficulties because no contributor had an account in GitLab. To be precise, the email address that identified each Phabrictor contributor didn’t already exist for any GitLab contributor. If GitLab had an account with the same email address as an account being imported, the system would have issued an error and prevented Forgerie from importing the contributor’s commits.

A few implementation details

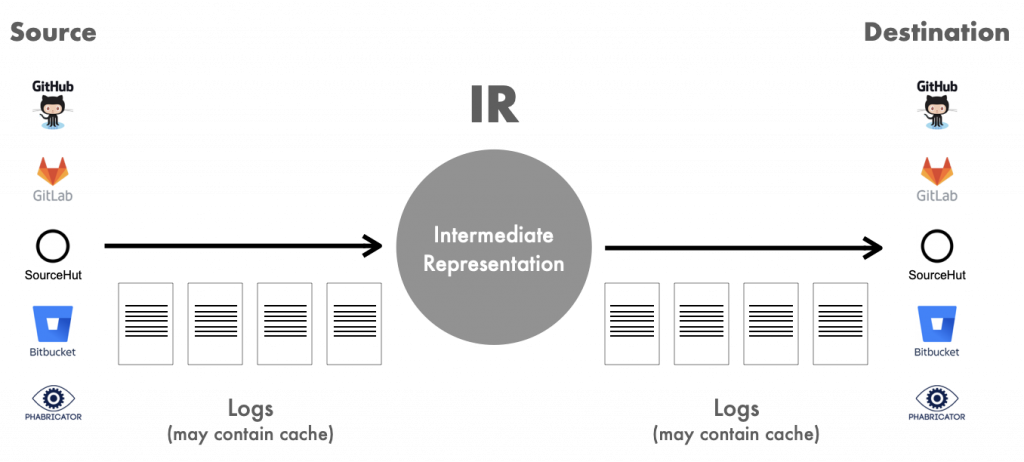

Forgerie carries out a migration by creating a log of everything that happened in the source repository, and replaying the log in the target forge. Phabricator uses a classic LAMP stack, storing all repository information into a MySQL database. Forgerie queries this database to retrieve each item in order, then invokes the GitLab API to create the item there.

The GitLab API is relatively slow for those particular types of request, requiring one or two seconds for each request, and repositories can contain tens of thousands of items when you count all the merges, comments, etc. So you can expect a migration to take 24 hours or more.

Long runs call for checkpoints and restarts. When Duncan designed the simple version of Forgerie for him to run just once, he figured he could just restart the run if it failed. Later he realized that restarting after 23 hours became unacceptable.

The log solves this problem through a kind of simple transaction. You can conceive of the migration as moving through three stages (Figure 1). In the first stage, items are in the old platform but not the log. In the second stage, Forgerie adds the items to the log. In the third stage, items are safely loaded into the destination platform and can be removed from the log. Should the job fail, the user can restart it from the beginning of the log.

A classic issue with transactions arises with a log: Suppose an item has just entered the target forge but Forgerie did not have a chance to remove the item from the log before a failure. The item exists in both the target repository and the log, so when Forgerie starts up again, the item will be added a second time to the repository. Forgerie developers do not have to worry about this happening because the insertions are idempotent. The second insertion overwrites the first with no corruption of information.

Assessing the Forgerie project

The Forgerie code base is surprisingly small–a total of 2,726 lines, divided as follows:

• Core (shared) code: 350 lines

• Phabricator-specific code: 1,233 lines

• GitLab-specific code: 1,143 lines

No platform lives forever. Amazing as the capabilities of GitHub and

GitLab are—and they continue to evolve—there will come a time when developers decide they have to pick up and move their code to some glorious new way of working. Forgerie tries to make migration as painless as possible.

Thanks to Andy Oram for assistance drafting this post, to Jim McGowan for making the diagrams, and to Antoine R. Dumont of Software Heritage for contributing technical improvements to the Forgerie project.